Table of Contents

Introduction

Let’s travel back to a simpler time when all everyone talked about in machine learning were SVMs and boosted trees, while Andrew Ng introduced neural networks as a neat party hat trick you would probably never use in practice1.

The year is 2012, and computer-vision based competition ImageNet is set to be once again won by the newest ensemble of kernel methods. That is, of course, until a couple of researchers unveiled AlexNet2, having almost two times lower error rate than the competition, by using what we now commonly refer to as “deep learning.”

Many people point to AlexNet as one of the most important scientific breakthroughs of the decade, certainly one that helped change the landscape of ML research. However, it does not take much to realize that under the hood, it is “just” a combination of prior iterative improvements, many dating back to the early nineties. At its core, AlexNet is “just” a modified LeNet3 with more layers, better weight initialization, activation function, and data augmentation.

Tools in ML Research

So what made AlexNet stand out so much? I believe the answer lies in the tools researchers had at their disposal, enabling them to run artificial neural networks on GPU accelerators, a relatively novel idea at the time. In fact, Alex Krizhevsky’s former colleagues recall that many meetings before the competition consisted of Alex describing his progress with the CUDA quirks and features.

Now let us travel back to 2015 when ML research article submissions started blowing up across the board, including (re-)emergence of many now promising approaches such as generative adversarial learning, deep reinforcement learning, meta-learning, self-supervised learning, federated learning, neural architecture search, neural differential equations, neural graph networks, and many more.

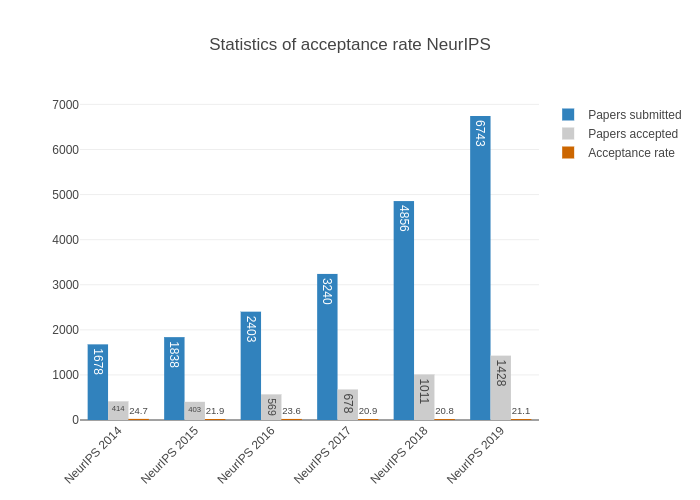

Image via Charrez, D. (2019).

Image via Charrez, D. (2019).

One could claim that this is just a natural outcome of the AI hype. However, I believe a significant factor was the emergence of the second generation of general-purpose ML frameworks such as TensorFlow4 and PyTorch5, along with NVIDIA going all-in on AI. The frameworks that existed before, such as Caffe6 and Theano7, were challenging to work with, and awkward to extend, which slowed down the research and development of novel ideas.

A Need for Innovation

TensorFlow and PyTorch were undoubtedly a net positive, and the teams worked hard to improve the libraries. Recently, they delivered TensorFlow 2.0 with a more straightforward interface along with eager mode8, and PyTorch 1.0 with JIT compilation of the computation graph9 as well as support for XLA10 based accelerators such as TPUs11. However, these frameworks are also beginning to reach their limits, forcing researchers into some paths while closing doors on others, just like their predecessors.

High-profile DRL projects such as AlphaStar12 and OpenAI Five13 not only utilized large-scale computational clusters but also pushed the limits of deep learning architecture components by combining deep transformers, nested recurrent networks, deep residual towers, among others.

In his interview with The Times newspaper, Demis Hassabis has stated that DeepMind will be focusing on applying AI directly for scientific breakthroughs. We can already see a glimpse of that shift in direction with some of their recent Nature articles on neuroscience14 and protein folding15. Even a brief skim through the publications is enough to see that the projects required some unconventional approaches when it comes to engineering.

At NeurIPS 2019, probabilistic programming and bayesian inference were hot topics, especially uncertainty estimation and causal inference. Leading AI researchers presented their visions on what the future of ML might look like. Notably, Yoshua Bengio described transitioning to system 2 deep learning with out-of-distribution generalization, sparse graph networks, and causal reasoning.

To summarize, some of the requirements for next-gen ML tools are:

- fine-grained control flow use

- non-standard optimization loops

- higher-order differentiation as a first-class citizen

- probabilistic programming as a first-class citizen

- support for multiple heterogeneous accelerators in one model

- seamless scalability from a single machine to gigantic clusters

Ideally, the tools should also maintain a clean, straightforward, and extensible API, enabling scientists to research and develop their ideas rapidly.

The Next Generation

The good news is that many candidates already exist today, emerging in response to the needs in scientific computing. From experimental projects like Zygote.jl16 to even specialized languages, e.g. Halide17 and DiffTaichi18. Interestingly, many projects draw inspiration from the fundamental works done by researchers in the auto-diff community19, which evolved in parallel to ML.

Many of them were featured at the recent NeurIPS 2019 workshop on program transformations. The two I am most excited about are S4TF20 and JAX21. They both tackle the task of making differentiable programming into an integral part of the toolchain, but in their own ways, almost orthogonal to each other.

Swift for TensorFlow

As the name suggests, S4TF tightly integrates the TensorFlow ML framework with the Swift programming language. A vote of confidence for the project is that it is led by Chris Lattner, who has authored LLVM22, Clang23, and Swift itself.

Swift is a compiled programming language, and one of its primary selling points is the powerful type system that is static and inferred. What the last part means in simpler terms is that Swift encompasses ease of use in languages like Python with code validations and transformations at compile-time, e.g., as in C++.

let a: Int = 1

let b = 2

let c = "3"

print(a + b) // 3

print(b + c) // compilation (!) error

print(String(b) + c) // 23

Swift features enable the S4TF team to meet quite a few requirements in the next-generation list by having analysis, verification, and optimization of the computation graph executed with efficient algorithms during compilation.

Crucially, the handling of automatic differentiation is off-loaded to the compiler.

struct Linear: Differentiable {

var w: Float

var b: Float

func callAsFunction(_ x: Float) -> Float {

return w * x + b

}

}

let f = Linear(w: 1, b: 2)

let 𝛁f = gradient(at: f) { f in f(3.0) }

print(𝛁f) // TangentVector(w: 3.0, b: 1.0)

let 𝛁f2 = gradient(at: f) { f in f([3.0]) } // compilation (!) error

// error: cannot convert value of type '[Float]' to expected argument type 'Float'

Of course, TensorFlow itself is very well supported in this case.

import TensorFlow

struct Model: Layer {

var conv = Conv2D<Float>(filterShape: (5, 5, 6, 16), activation: relu)

var pool = MaxPool2D<Float>(poolSize: (2, 2), strides: (2, 2))

var flatten = Flatten<Float>()

var dense = Dense<Float>(inputSize: 16 * 5 * 5, outputSize: 100, activation: relu)

var logits = Dense<Float>(inputSize: 100, outputSize: 10, activation: identity)

@differentiable

func callAsFunction(_ input: Tensor<Float>) -> Tensor<Float> {

return input.sequenced(through: conv, pool, flatten, dense, logits)

}

}

var model = Model()

let optimizer = RMSProp(for: model, learningRate: 3e-4, decay: 1e-6)

for batch in CIFAR10().trainDataset.batched(128) {

let (loss, gradients) = valueWithGradient(at: model) { model in

softmaxCrossEntropy(logits: model(batch.data), labels: batch.label)

}

print(loss)

optimizer.update(&model, along: gradients)

}

On the other hand, if a critical feature is proving to be difficult to implement, having intimate knowledge of the whole pipeline is particularly valuable. For example, the MLIR compiler framework is a direct result of the S4TF efforts.

While differentiable programming is the core goal, S4TF is much more than that with a plan to support the infrastructure for various next-gen ML tools such as debuggers. For example, imagine an IDE warning a user that the custom model computation always results in a zero gradient without even executing it.

Python has an incredible community built around scientific computing and the S4TF team has explicitly taken the time to embrace it via interoperability.

import Python // All that is necessary to enable the interop.

let np = Python.import("numpy") // Can import any Python module.

let plt = Python.import("matplotlib.pyplot")

let x = np.arange(0, 10, 0.01)

plt.plot(x, np.sin(x)) // Can use the modules as if inside Python.

plt.show() // Will show the sin plot, just as you would expect.

This project is a significant undertaking and still has some ways to go before being ready for production.

However, this is a great time to give it a try for both engineers and researchers and potentially contribute to its development.

Work on S4TF has already produced interesting scientific advancements at the intersection of programming language and auto-diff theory24.

One thing that especially stands out for me about S4TF is their approach to community outreach. For example, the core developers hold weekly design sessions, which are open for anyone interested to join and even participate.

To learn more about Swift for TensorFlow, here are some useful resources:

- Fast.ai’s Lessons 13 and 14

- Design Doc: Why Swift For TensorFlow?

- Model Training Tutorial

- Pre-Built Google Colab Notebook

- Swift Models for Popular Architectures in DL and DRL

JAX

JAX is a collection of function transformations such as just-in-time compilation and automatic differentiation, implemented as a thin wrapper over XLA with an API that is essentially a drop-in replacement for NumPy and SciPy. In fact, one way to get started with JAX is to think of it as an accelerator backed NumPy.

import jax.numpy as np

# Will be seamlessly executed on an accelerator such as GPU/TPU.

x, w, b = np.ones((3, 1000, 1000))

y = np.dot(w, x) + b

Of course, in reality, JAX is much more than that. To many, it might seem that the project appeared out of thin air, but the truth is that it is an evolution of over five years of research spanning across three projects. Notably, JAX emerged from Autograd – a research endeavor into AD of native program code – generalizing on its core ideas to support arbitrary transformations.

def f(x):

return np.where(x > 0, x, x / (1 + np.exp(-x)))

# Note: same singular style for the API entry points.

jit_f = jax.jit(f) # Will be 10-100x faster, depending on the accelerator.

grad_f = jax.grad(f) # Will work as expected, handling both branches.

Aside from the grad and jit discussed above, there are two more excellent examples of JAX transformations, helping

users to batch-process their data via auto-vectorization of batch dimension (vmap) or across multiple devices (pmap).

a = np.ones((100, 300))

def g(vec):

return np.dot(a, vec)

# Suppose `z` is a batch of 10 samples of 1 x 300 vectors.

z = np.ones((10, 300))

g(z) # Will not work due to (batch) dimension mismatch (100x300 x 10x300).

vec_g = jax.vmap(g)

vec_g(z) # Will work, efficiently propagating through batch dimension.

# Manual solution requires "playing" with matrix transpositions.

np.dot(a, z.T)

These features might seem confusing at first, but after some practice, they turn into an irreplaceable part of a researcher’s toolbox. They have even inspired recent development of similar functionality in both TensorFlow and PyTorch.

For the time being, JAX authors seem to be sticking to their core competency when it comes to developing new features. Of course, a reasonable approach but is also the cause for one of its main drawbacks: lack of built-in neural network components, aside from the proof-of-concept Stax.

Adding higher-level features is something where end-users can potentially step in and contribute, and given JAX’s solid foundation, the task might be easier than it seems. For example, there are now two “competing” libraries built on top of JAX, both developed by Google researchers, with differing approaches: Trax and Flax.

# Trax approach is functional.

# Note: params are stored outside and `forward` is "pure".

import jax.numpy as np

from trax.layers import base

class Linear(base.Layer):

def __init__(self, num_units, init_fn):

super().__init__()

self.num_units = num_units

self.init_fn = init_fn

def forward(self, x, w):

return np.dot(x, w)

def new_weights(self, input_signature):

w = self.init_fn((input_signature.shape, self._num_units))

return w

# Flax approach is object-oriented, closer to PyTorch style.

import jax.numpy as np

from flax import nn

class Linear(nn.Module):

def apply(self, x, num_units, init_fn):

W = self.param('W', (x.shape[-1], num_units), init_fn)

return np.dot(x, W)

Even though some might prefer a singular way, endorsed by core developers, having a diversity of methods is a good indicator that the technology is sound.

There are also some directions in research where JAX features especially shine. For example, in meta-learning, one common approach to training a meta-learner is by computing the gradients of the inputs. An alternative method for computing gradients – forward-mode auto-differentiation – is necessary to solve this task efficiently, which is supported out-of-the-box in JAX but is either non-existent or an experimental feature in other libraries.

JAX is perhaps more polished and production-ready than its S4TF counter-part and some of the recent developments coming out of Google Research rely on it, such as Reformer – a memory-efficient Transformer model capable of handling context windows of a million words while fitting on a consumer GPU25, and Neural Tangents – a library for complex neural networks of infinite width26.

The library is further embraced by the broader scientific computing community, used for works in molecular dynamics27, probabilistic programming28, and constrained optimization29, among others.

To get started with JAX and for further reading, please review the following:

- Talk: Overview by Skye Wanderman-Milne, a core developer (starts at 44:26)

- Notebook: Quickstart, going over fundamental features

- Notebook: Cloud TPU Playground

- Blog: You don’t know JAX

- Blog: Massively parallel MCMC with JAX

- Blog: Differentiable Path Tracing on the GPU/TPU

Conclusion

ML research is starting to hit the limits of the tools we currently have at our disposal, but some new and exciting candidates are right around the corner, such as JAX and S4TF. If you feel yourself to be more of an engineer than a researcher and wonder whether there is even a place for you at the ML table, hopefully, the answer is clear: right now is the perfect time to get into it. Moreover, you have an opportunity to participate on the ground floor of the next generation of ML tools!

Note that this does not mean TensorFlow or PyTorch are going anywhere, not in the near future. There is still much value in these mature, battle-tested libraries. After all, both JAX and S4TF have parts of TensorFlow under their hoods. But if you are about to start a new research project or if you feel that you are working around library limitations more than on your ideas, then maybe give them a try!

References

- Ng, A. (2011). Week 4: Neural Networks. COURSERA: Machine Learning. ↑

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. ↑

- LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y., & Haffner, P. (1998). Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE. ↑

- Abadi, M., Barham, P., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Davis, A., Dean, J., … & Kudlur, M. (2016). Tensorflow: A system for large-scale machine learning. In 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation. ↑

- Paszke, A., Gross, S., Massa, F., Lerer, A., Bradbury, J., Chanan, G., … & Desmaison, A. (2019). PyTorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. ↑

- Jia, Y., Shelhamer, E., Donahue, J., Karayev, S., Long, J., Girshick, R., … & Darrell, T. (2014). Caffe: Convolutional architecture for fast feature embedding. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM international conference on Multimedia. ↑

- Bergstra, J., Breuleux, O., Bastien, F., Lamblin, P., Pascanu, R., Desjardins, G., … & Bengio, Y. (2010). Theano: a CPU and GPU math expression compiler. In Proceedings of the Python for scientific computing conference. ↑

- Agrawal, A., Modi, A. N., Passos, A., Lavoie, A., Agarwal, A., Shankar, A., … & Cai, S. (2019). Tensorflow eager: A multi-stage, python-embedded dsl for machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.01855. ↑

- Contributors, PyTorch. (2018). Torch script. URL https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/jit.html ↑

- Leary, C., & Wang, T. (2017). XLA: TensorFlow, compiled. TensorFlow Dev Summit. ↑

- Jouppi, N. P., Young, C., Patil, N., Patterson, D., Agrawal, G., Bajwa, R., … & Boyle, R. (2017). In-datacenter performance analysis of a tensor processing unit. In 44th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture. ↑

- Vinyals, O., Babuschkin, I., Czarnecki, W. M., Mathieu, M., Dudzik, A., Chung, J., … & Silver, D. (2019). Grandmaster level in StarCraft II using multi-agent reinforcement learning. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1724-z ↑

- Berner, C., Brockman, G., Chan, B., Cheung, V., Dębiak, P., Dennison, C., … & Józefowicz, R. (2019). Dota 2 with Large Scale Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.06680. ↑

- Dabney, W., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Uchida, N., Starkweather, C. K., Hassabis, D., Munos, R., & Botvinick, M. (2020). A distributional code for value in dopamine-based reinforcement learning. Nature. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1924-6 ↑

- Senior, A., Evans, R., Jumper, J., Kirkpatrick, J., Sifre, L., Green, T., … & Penedones, H. (2020). Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature. ↑

- Innes, M. (2018). Don’t Unroll Adjoint: Differentiating SSA-Form Programs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.07951. ↑

- Ragan-Kelley, J., Barnes, C., Adams, A., Paris, S., Durand, F., & Amarasinghe, S. (2013). Halide: a language and compiler for optimizing parallelism, locality, and recomputation in image processing pipelines. In ACM Sigplan Notices. ↑

- Hu, Y., Anderson, L., Li, T. M., Sun, Q., Carr, N., Ragan-Kelley, J., & Durand, F. (2019). DiffTaichi: Differentiable Programming for Physical Simulation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.00935. ↑

- Baydin, A. G., Pearlmutter, B. A., Radul, A. A., & Siskind, J. M. (2017). Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a survey. The Journal of Machine Learning Research. ↑

- Wei, R., & Zheng, D. (2018). Swift for TensorFlow. URL https://github.com/tensorflow/swift. ↑

- Bradbury, J., Frostig, R., Hawkins, P., Johnson, M. J., Leary, C., Maclaurin, D., & Wanderman-Milne, S (2018). JAX: composable transformations of Python+ NumPy programs. URL https://github.com/google/jax. ↑

- Lattner, C. (2002). LLVM: An infrastructure for multi-stage optimization. Masters thesis, University of Illinois. ↑

- Lattner, C. (2008). LLVM and Clang: Next generation compiler technology. In The BSD conference. ↑

- Vytiniotis, D., Belov, D., Wei, R., Plotkin, G., & Abadi, M. (2019). The Differentiable Curry. ↑

- Kitaev, N., Kaiser, L., and Levskaya, A. (2020). Reformer: The Efficient Transformer. In International Conference on Learning Representations. ↑

- Novak, R., Xiao, L., Hron, J., Lee, J., Alemi, A., Sohl-dickstein, J., & Schoenholz, S. (2020). Neural Tangents: Fast and Easy Infinite Neural Networks in Python. In International Conference on Learning Representations. ↑

- Schoenholz, S., & Cubuk, E. (2020). JAX, MD End-to-End Differentiable, Hardware Accelerated, Molecular Dynamics in Pure Python. Bulletin of the American Physical Society. ↑

- Phan, D., Pradhan, N., & Jankowiak, M. (2019). Composable Effects for Flexible and Accelerated Probabilistic Programming in NumPyro. ↑

- Bacon, P. L., Schäfer, F., Gehring, C., Anandkumar, A., & Brunskill, E. A Lagrangian Method for Inverse Problems in Reinforcement Learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. ↑